The poison in beauty

Have a look at the two pictures below and try to express what you see in a few sentences.

Well, the photographs are not particularly stunning or well-framed. An agricultural landscape, flat mostly with a backdrop of low hills. Not even a spectacular day, with grey clouds in the sky and signs of recent rainfall moistening the soil. Autumn, by the colour of the corn plants in one image. Carrots almost ready for harvesting in the other.

In sum, absolutely unremarkable. I took the pictures on 9 October 1993 with no other ambition than to record a few facts. Striking in the landscape-oriented picture are the barren furrows and, in the foreground, an untended plot of land with wild grass and carrot plants with spots of brown soil between them. The vertical photograph emphasises the brown soil and low density of carrot plants. A wood-brownish discolouration separates the lighter green vegetation that stretches to the distant hill from the foreground.

Nothing will grow in the bare furrows and the brownish fleck. Around these places farmers harvest only meagre yields from the otherwise fertile sandy loam soil. This has been the case for the past 100 years and is likely to remain so for generations to come.

I took these pictures and several other ones somewhere halfway between Langemark-Poelkapelle and Houthulst north of Ypres in Flanders, Belgium. Langemark is the small place near which German Imperial forces launched the first chlorine attack against the Ypres Salient on 22 April 1915. Six years later, on 24 April 1921, Belgian authorities contracted a subsidiary of a British firm, F. N. Pickett et Fils to dispose of huge volumes of munitions, including chemical shells. The contract specified how the company could dispose of the toxic chemicals:

‘The liquid, corrosive and toxic compounds must be destroyed on-site, removed, transformed into harmless products, or disposed of in a borehole with a depth of 2.50 metres after they have been neutralized. The holes will be filled and closed by the Pickett company, at its expense, to the complete satisfaction of the Belgian authorities’.

As I wrote in my study for SIPRI on the early disposal of chemical weapons (CW) in Belgium, Pickett may not have followed those instructions. Until today local people believe that nothing will grow in some parts of the former disposal site because back then workers had simply poured the toxic chemicals into the soil.

Another landscape lost its innocence to armaments and weapons disposal.

Project Cleansweep

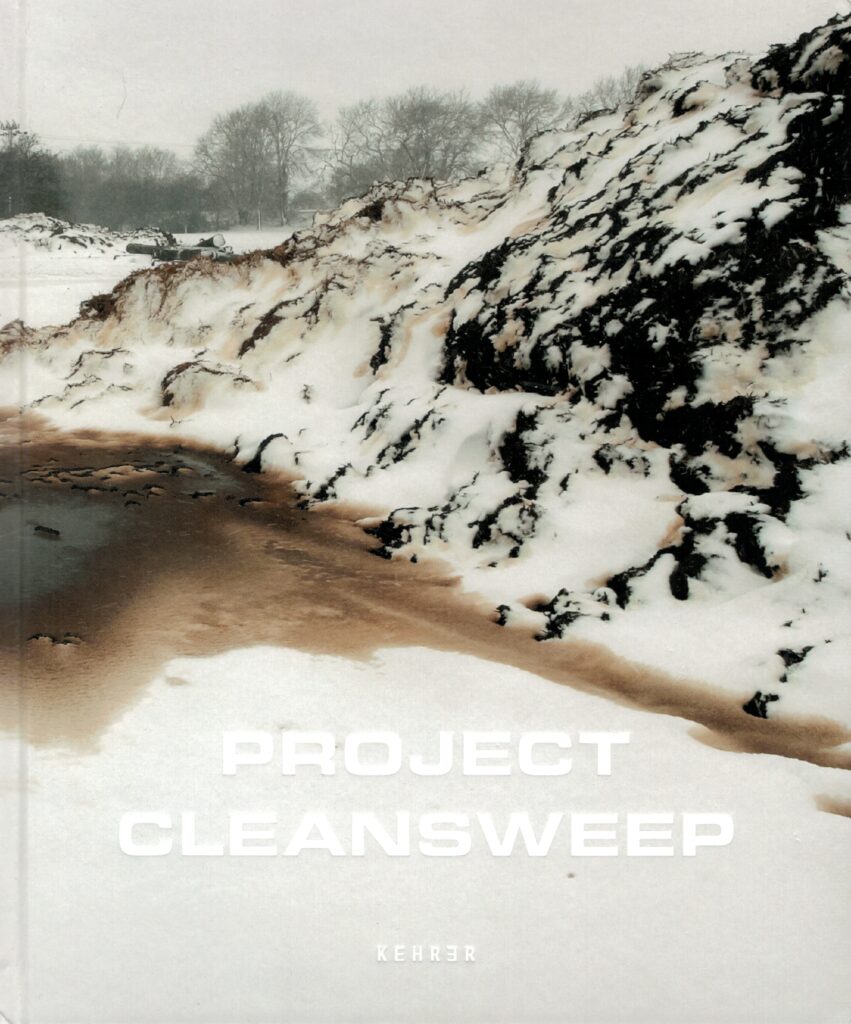

Opening the book ‘Project Cleansweep’ by Irish photographer Dara McGrath made me think back of that day in October 1993 when I pondered in amazement how chemical warfare agents were causing enduring harm to the environment (then) 75 years after the end of the First World War.

In July 2011, the UK Ministry of Defence (MoD) made public an internal briefing document on residual contamination at former CW production, storage, handling and disposal sites after freedom of information requests. Rather than reassuring the public that the identified sites posed no significant harm to public safety or the environment, it caused a stir. I can imagine how the press reports must have got Dara ruminating over landscapes untouched for many decades yet hiding a poisonous legacy whose tell-tale signs only few in the know could understand. The site identification exercise undertaken in 2007 the MoD had called ‘Project Cleansweep’.

The book comprises four parts, each corresponding to a major aspect of the armament dynamic: manufacture, storage, testing and dispersal. Each part also pauses at a major site that exemplified the activity. Rhydymwyn on the northern coast of Wales was where the British had their largest production and storage site for bulk chemical warfare agents. Harpur Hill in Derbyshire was the biggest CW storage site during the Second World War and later served to dispose of German CW via incineration or destruction with bleach. Gruinard Island on Scotland’s northwest coast is the well-known site of tests with anthrax spores during the Second World War. It remained off limits to the public until 1990. And finally, Lyme Bay in Dorset on the south coast of England was a designated site for weapon trials, which included the offshore release of live bacteria and simulants for biological weapons.

While the MoD briefing paper listed only 14 sites, Dara visited 92 for his project.

Constructing the narrative

Dara’s photographs are beautifully crafted. The landscapes leave impressions; composition demands closer attention. Other expanses are carved up by human constructions left for the elements to wither them, or, sometimes, hint at future construction projects. Derelict buildings, whether seen from the inside, suggested by some abandoned equipment, or part of a landscape, he has carefully manipulated for lighting, contrast, and saturation. Some images suggest industrial wasteland, yet stunning in beauty.

For a book seeking to document the legacy of the UK’s chemical and biological warfare programmes, the reader will not see a single photograph of a chemical or biological weapon (CBW). The direct link between a picture and the book’s main theme Dara establishes through short texts identifying the location and offering some narrative.

Gradually the reader’s consciousness grows that the post-military landscape remains with us. Only a lack of historical awareness prevents us from interpreting the relics of military activity relating to the manufacture, storage and testing of CBW. A striking example is the picture of a lake at Harpur Hill known locally as the ‘Blue Lagoon’ because of the toxic water’s colour. It instantly reminded me of Kerið in Iceland, a caldera filled with azure water whose hue varies with the light’s angle of incidence and surrounded by almost fluorescent moss. There is indeed poison in beauty; only in the latter case the origin is volcanic rather than human.

We know that the agents are extremely dangerous, yet we are mostly unaware of the sites where they were handled many decades before. For example, of the four locations Dara presents in greater detail, the past CBW-related activities at three go unmentioned in Wikipedia. Only the entry for Gruinard Island carries several paragraphs on the anthrax dissemination experiments and the subsequent decontamination operation.

As the author explains at one point, locals may not learn that something is amiss until an unusual cluster of health conditions or physical deformities emerges. The silent danger of lingering poison he accentuates by inserting old and new pictures of unsuspecting people going about their business or enjoying the pleasures of relaxation where previously weapons had been manufactured or tested, and interspersing his personal narrative with poignant archive photos and materials, or a contemporary press clipping.

In conclusion…

‘Project Cleansweep’ captivates. Not just because of the quality of photography but mainly because of the learning process. As I progressed, I found myself going back and forth through the book comparing impressions, looking for parallels, and each time discovering new aspects emerging from the photographs.

A most satisfying experience on different levels even in the realisation that the poison legacies will insult nature for generations to come.

Book review:

Dara McGrath (2020), Project Cleansweep (Heidelberg: Kehrer Verlag, 2020), 216p.

https://daramcgrath.com/publications/