CW incidents alleged by the Syrian government: an industrial chemical as likely cause?

My previous posting (16 November) presented the findings by the Fact-Finding Mission (FFM) of the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) concerning allegations of the use of chlorine as a chemical weapon in Syria’s Idlib Governorate. The FFM concluded that the incidents likely involved the use of a toxic chemical containing the element chlorine as a weapon.

This report was one of three that the Technical Secretariat of the OPCW transmitted to states party to the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC) for consideration at a special session of the Executive Council on 23 November. The other two reports address allegations of mustard agent use at Marea in northern Syria and chlorine attacks against Syrian government forces around Damascus.

This contribution focusses on the latter investigation. Syria submitted four Notes Verbales alleging a total of 26 chemical weapon (CW) events resulting in 432 casualties. The first reported incident dates back as far as 19 March 2013; the most recent ones took place in May 2015.

The investigative team deployed to Syria on 1 June, 1 August and 13 October. It has not yet finalised its investigation and the interim report circulating among CWC states parties focusses primarily on one incident at Jobar (‘Jober’ as spellt in the report), a municipality northeast of the old town of Damascus, on 29 August 2014. Although the investigation is ongoing, the FFM

is of the view that those affected in the alleged incident may have been exposed to some type of non-persistent, irritating airborne substance, following the surface impact of two launched objects.

However, based on the evidence presented by the Syrian National Authority, the medical records that were reviewed, and the prevailing narrative of all of the interviews, the FFM cannot confidently determine whether or not a chemical was used as a weapon.

The FFM was unable to identify a specific irritant, but believes an industrial chemical may offer the most plausible explanation for the reviewed symptoms. It as good as ruled out use of chlorine or nerve agents in Jobar on 29 August 2014.

Conclusions about some other incidents reported by the Syrian government will be part of the final report.

Allegations by the Syrian government

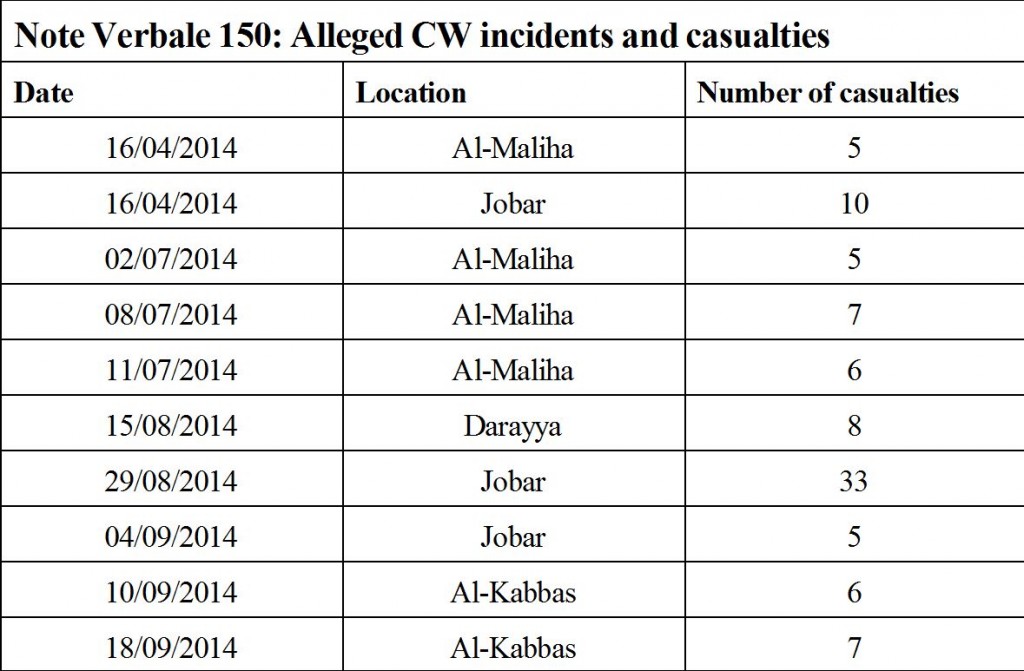

The Syrian Deputy Minister for Foreign Affairs and Expatriates, who also heads the Syrian CWC National Authority, submitted Note Verbale 150 to the Technical Secretariat on 15 December 2014. The document alleges 10 separate CW incidents in four Damascus neighbourhoods between April and September 2014 that resulted in 92 casualties, all among military personnel.

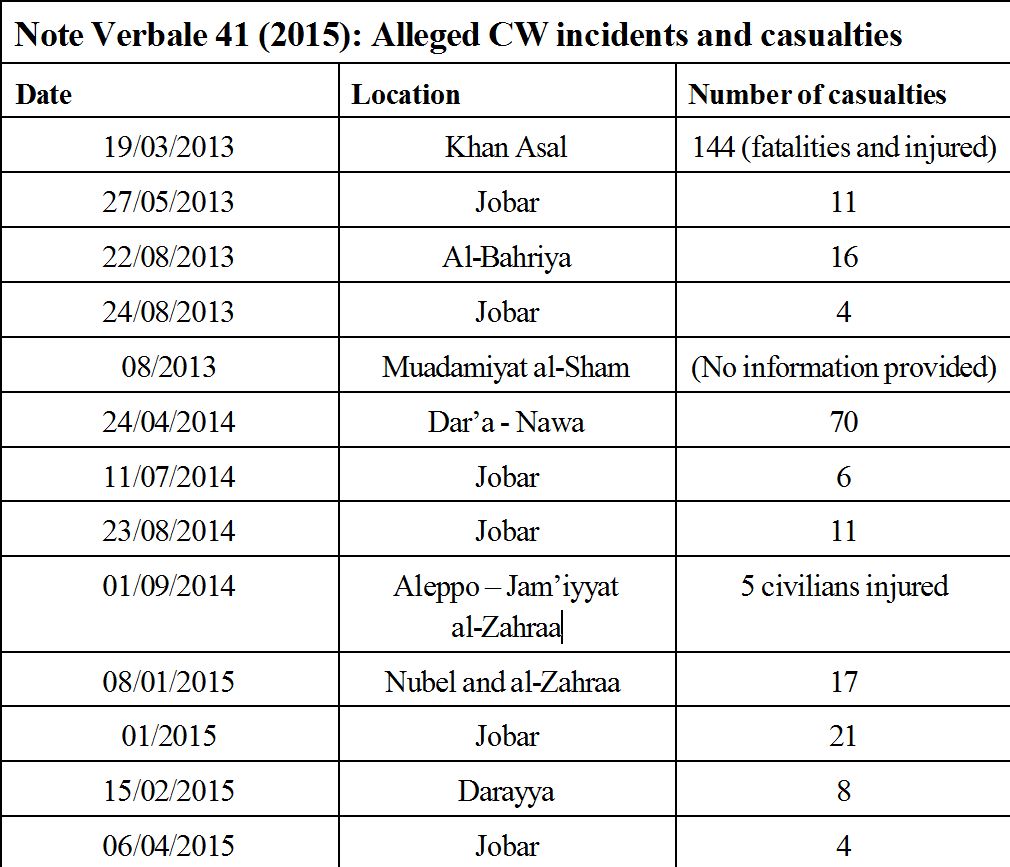

Syria’s Permanent Mission to the OPCW delivered Note Verbale 41 to the Technical Secretariat on 29 May 2015. It lists 13 separate incidents, five of which preceded Syria’s accession to the CWC, four whose dates fall within the date range of Note Verbale 150 and an additional four that took place early in 2015. These attacks allegedly occurred in the areas surrounding Aleppo and Damascus. Although this note is less explicit about the nature of the victims, it lists a minimum of 317 casualties, including at least five civilians. The document offers details on suspected chlorine use. The Syrian authorities requested members of the advance team (who deployed to Syria from 25 to 29 May 2015) that these events be included in the scope of the FFM. That, however, proved impossible without a new mandate covering additional events.

It is interesting to note that some of the incidents predating Syria’s accession to the CWC had already been examined by the UN investigative team in August and September 2013. That investigation corroborated allegations of CW use at Khan Al Asal and described the incident as ‘a rapidly onsetting [sic] mass intoxication by an organophosphorous compound in the morning of the 19 March 2013’, but added that ‘the release of chemical weapons at the alleged site could not be independently verified in the absence of primary information on delivery systems and of environmental and biomedical samples collected and analysed under the chain of custody’.

The two other incidents alleged in Note Verbale 41 took place immediately after the infamous Ghouta attack of 21 August 2013 and had also been investigated by the UN team. Of the one at Al-Bahriya (spelt as Bahhariyeh in the UN report) on 22 August 2013, the UN team could not corroborate the allegation. Blood samples all tested negative for any known signatures of chemical warfare agents.

With respect to the incident at Jobar on 24 August 2013 the UN report confirmed a ‘relatively small scale’ use of sarin against soldiers. However, again ‘in the absence of primary information on the delivery system(s) and environmental samples collected and analysed under the chain of custody, the United Nations Mission could not establish the link between the victims, the alleged event and the alleged site’.

Note Verbale 41 is equally intriguing for the absence of several other alleged incidents between March and September 2013 investigated by the UN team. These presumably concerned the investigation requests by France, the UK and the USA included in the mandate of the investigators by UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon. Note Verbale 41 also lists some incidents not addressed by the UN team.

It is clear that the OPCW has all but ignored the allegations prior to Syria’s accession to the CWC.

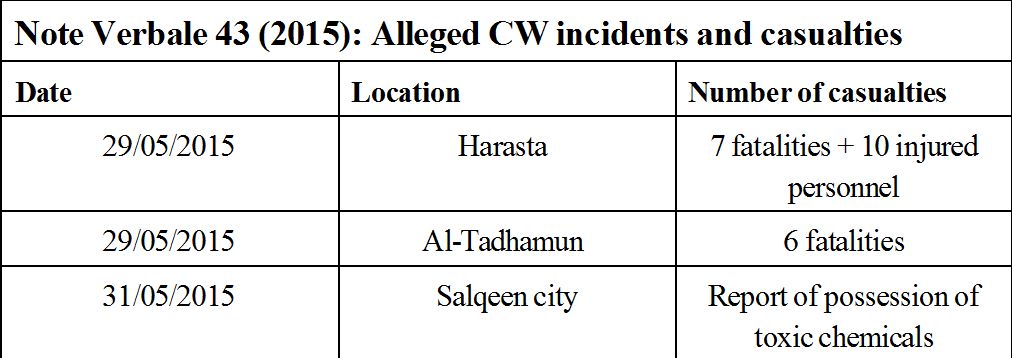

Note Verbale 43 dated 3 June 2015 reports three additional incidents in May 2015.

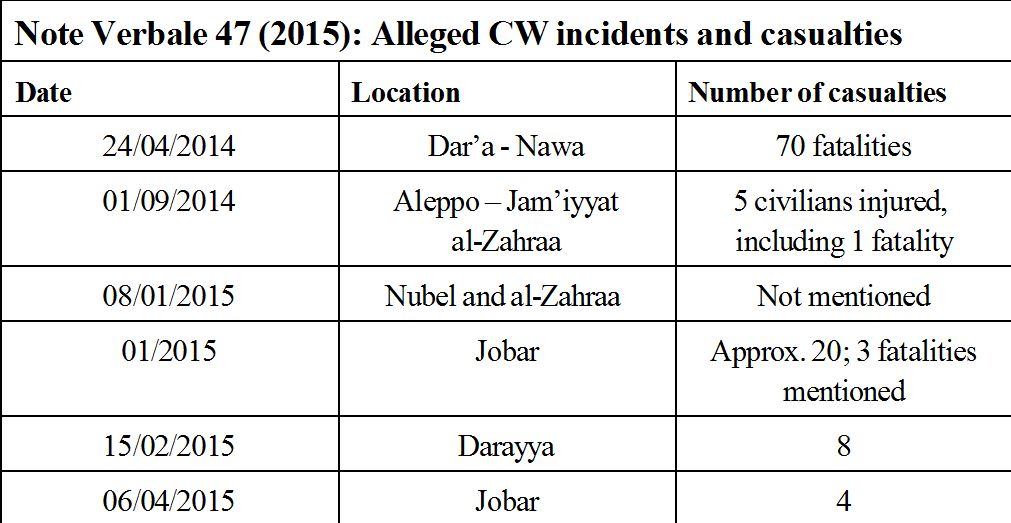

Note Verbale 47 dated 15 June 2015 comprises six incidents that had already been mentioned in Note Verbale 41, but offers more background information, including greater detail on events, greater precision of sites of alleged attacks, and references to symptoms suffered by the exposed victims.

Based on Notes Verbales 41, 43 and 47, the FFM was dispatched for a second investigative deployment.

Assessment of the alleged incidents

In view of the large number of allegations, the FFM was unable to investigate each one or had to sequence investigations based on the severity of allegations. Thus it was agreed with the Syrians that the FFM would focus initially on the Jobar event of 29 August 2014 because it involved the highest number of reported casualties in Note Verbale 150.

After receipt of the additional Notes Verbales, the FFM proposed additional investigation of two allegations in 2014 and one in 2015. Based on additional data supplied by the Syrian government, the investigative team eventually looked into five reported events during its second deployment: Al-Maliha on 16 April and 11 July 2014, Al-Kabbas on 10 September 2014, Nubel and al-Zahraa on 8 January 2015, and Darayya on 15 February 2015.

The report of 29 October indicates that the FFM completed its mandate for the Jobar investigation. It expresses considerable frustration about the dearth of additional evidence to support the allegation:

The FFM is of the opinion that it would have been able to be more precise in its findings if further objective evidence, complementing what was provided by the authorities of the Syrian Arab Republic, had been made available to the team. The FFM was not able to obtain hard evidence related to this incident, either because it was unavailable or because it was not generated in the first place. The lack of hard evidence precluded the FFM from gathering further facts in a definitive way.

While interviews with soldiers point to the possibility ‘of exposure to some type of non-persistent, airborne irritant secondary to the surface impact of two launched objects’, the FFM could not confidently determine whether such exposure might have resulted from the payload of the projectiles or from another source (propellant, a chemical stored in the area of impact, detonation products, etc.) because of insufficient evidence presented by Syria, insufficient details in reviewed medical records, and inconsistencies in the narratives of interviewees. So, the FFM concluded that:

while the general clinical presentation of those affected in the incident is consistent with brief exposure to any number of chemicals or environmental insults, the visual and olfactory description of the potential irritant does not clearly implicate any specific chemical.

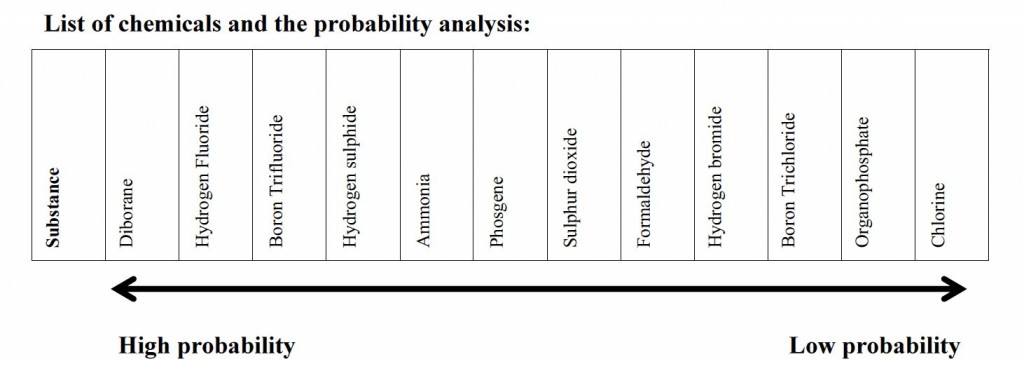

This particular investigation was also hampered by the delay of some nine months between the alleged incident and the start of the mission. Notwithstanding, the FFM all but ruled out chlorine and organophosphorous compounds (e.g., sarin) as agents responsible for the described symptoms. High on the list of probabilities figures diBorane, which besides use as a rocket propellant also has application in electronic industries and the vulcanisation of rubber. As the report notes, these uses make it ‘relevant to the interests of a militarized non-state actor [and it is] also readily available in the region’. Many of the reviewed symptoms appear consistent with exposure to this non-persistent and volatile chemical.

The report on the allegations raised by the Syrian government is preliminary. The Jobar investigation is in the process of finalisation. The other mentioned incidents also remain under investigation pending final analysis. The interim report only contains an overview of activities undertaken until October 2015. These findings will also be included in the final report.