Syria stands formally accused of violating the Chemical Weapons Convention

The Executive Council of the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) held its 94th session from 7–10 July. Prominent on the agenda was the determination by the Investigation and Identification Team (IIT) that ‘there are reasonable grounds to believe’ that Syrian government forces bear responsibility for several chemical weapon (CW) attacks at the end of March 2017.

The finding is the first time that the Technical Secretariat of the OPCW has formally charged a state party to the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC) with violating Article I, para. 1(b) to never under any circumstances use CW. The accusation is serious: few other provisions in the convention could be less ambiguous.

The 41-member Executive Council approved the Decision addressing the possession and use of chemical weapons by the Syrian Arab Republic by a large majority: 29 against 3 (with 9 abstentions). It opens the door to further investigation of war crimes and prosecution of individual perpetrators of such crimes under international law. It also sets the process in motion whereby parties to the CWC may hold another state party accountable for major treaty breaches. This would be a first in the 23-year history of the disarmament agreement.

The Investigation and Identification Team

The IIT is the youngest unit created within the Technical Secretariat to address questions of Syrian non-compliance with the CWC, the other two being the Declarations Assessment Team (DAT) and the Fact-Finding Mission (FFM). At the fourth special session of the Conference of the States Parties held in June 2018 OPCW members decided that (Document C-SS-4/DEC.3, 27 June 2018)

the [Technical] Secretariat shall put in place arrangements to identify the perpetrators of the use of chemical weapons in the Syrian Arab Republic by identifying and reporting on all information potentially relevant to the origin of those chemical weapons in those instances in which the OPCW Fact-Finding Mission in Syria determines or has determined that use or likely use occurred, and cases for which the OPCW-UN Joint Investigative Mechanism has not issued a report.

The IIT began its work in June 2019.

The decision limited the IIT’s scope of work in two ways. First, the FFM must have confirmed or deem past and present allegations of CW use in Syria credible. Since the OPCW Director-General formed the FFM in April 2014, the IIT cannot look into earlier allegations of CW use (e.g. the sarin attack in Ghouta on 21 August 2013, i.e. before the Syria became a party to the CWC). Also, it cannot review evidence of incidents published by other international forums (e.g. the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic under the auspices of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights) or submitted by non-governmental organisations. Second, allegations already assessed by the OPCW-UN Joint Investigative Mechanism (JIM) the IIT cannot revisit.

The JIM had been a UN Security Council (UNSC) initiative under Resolution 2235 (2015) to identify and hold accountable those responsible for CW attacks in Syria. Russia blocked the second one-year extension of the body’s mandate in November 2017 in response to the JIM report that held Syria responsible for the sarin attack against Khan Shaykhun seven months earlier. In response, France launched the International Partnership against Impunity for the Use of Chemical Weapons in January 2018. The initiative’s partners – all 28 members of the European Union and 38 other parties to the CWC – initiated the diplomatic drive that resulted in the June 2018 decision to establish the IIT.

Selection of incidents

In its first progress note to the Executive Council dated 28 June 2019, the IIT listed nine out of 33 possibly relevant incidents on which it was to focus its initial investigative work. It justified this selection based on the information gathered by the FFM, the number of casualties, the likelihood of retrieving additional information, and the chemical agent used. Besides the three attacks at Ltamenah, the list included Al-Tamanah, 12 April 2014; Kafr-Zita, 18 April 2014; Al-Tamanah, 18 April 2014; Marea, 1 September 2015; Saraqib, 4 February 2018; and Douma, 7 April 2018.

The IIT’s investigative report indicates an additional element for prioritisation, namely patterns of similar incidents. The cluster of chemical strikes against Ltamenah occurred within less than one week.

Its selection held a supplementary advantage, namely the JIM report on the sarin attack against nearby Khan Shaykhun four days later. Comparison of both documents by CWC parties would inevitably point to additional similarities and patterns including chemical markers of the sarin nerve agent, the attack mode, type of aircraft and bomb, and identification of the military airfields from which the ground-attack aircraft had departed.

The first IIT report

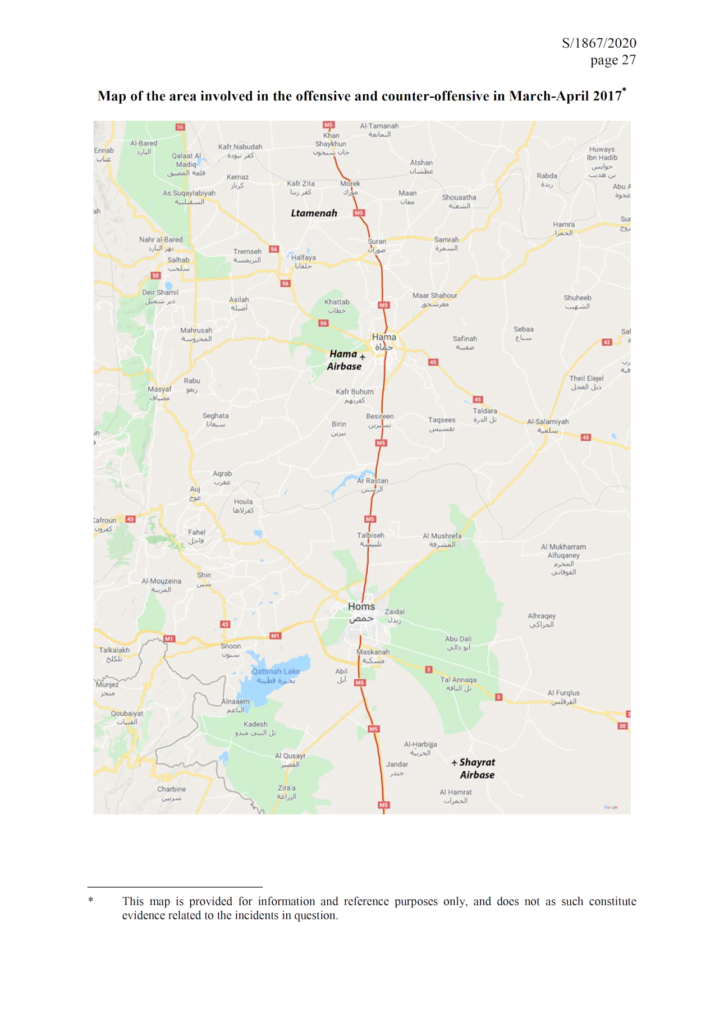

Insurgents launched a counteroffensive on 21 March 2017 to recapture Hama, a city south of the border between the Idlib and Hama Governorates in northwest Syria. North of Hama were two smaller towns then in rebel-occupied territory: Ltamenah (about 28 km) and Khan Shaykhun (about 36km, in Idlib). By the end of the month, government troops had blocked the offensive and began to push the insurgents back. The Syrian army reached the border with the Idlib Governorate and captured Latamenah at the end of April.

During the last week of March and the first week of April government forces struck Ltamenah three times with sarin and chlorine and Khan Shaykhun once with sarin. The latter attack was lethal with around 100 people reported killed due to exposure to the warfare agent. In its seventh report, the JIM concluded that it ‘is confident that the Syrian Arab Republic is responsible for the release of sarin at Khan Shaykhun on 4 April 2017’.

The IIT’s first investigative report, published on 8 April 2020, reviewed the FFM findings of the three preceding attacks at Ltamenah and concluded that

there are reasonable grounds to believe that:

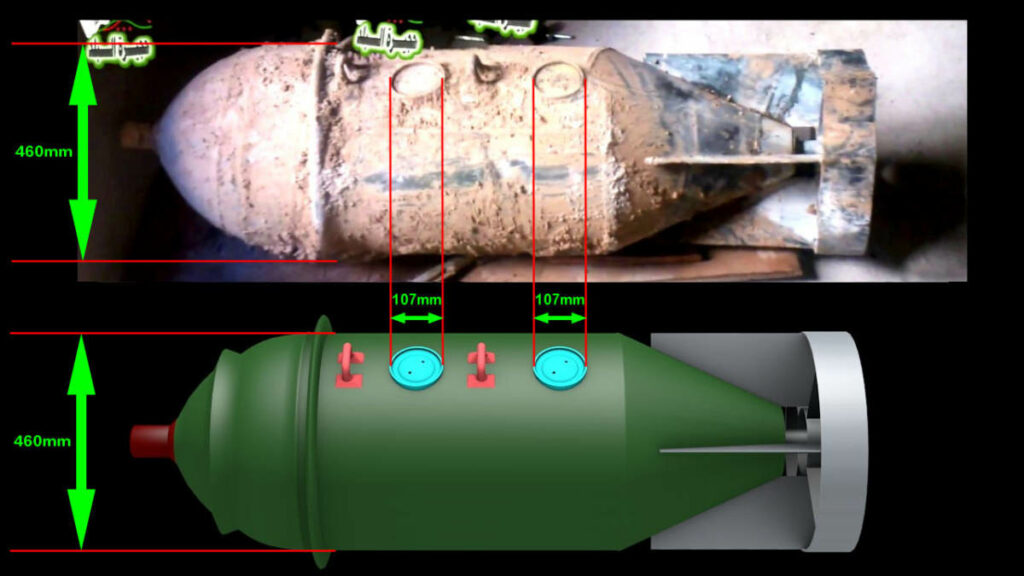

(a) At approximately 6:00 on 24 March 2017, an Su-22 military airplane belonging to the 50th Brigade of the 22nd Air Division of the Syrian Arab Air Force, departing from Shayrat airbase, dropped an M4000 aerial bomb containing sarin in southern Ltamenah, affecting at least 16 persons.

(b) At approximately 15:00 on 25 March 2017, a helicopter of the Syrian Arab Air Force, departing from Hama airbase, dropped a cylinder on the Ltamenah hospital; the cylinder broke into the hospital through its roof, ruptured, and released chlorine, affecting at least 30 persons.

(c) At approximately 6:00 on 30 March 2017, an Su-22 military airplane belonging to the 50th Brigade of the 22nd Air Division of the Syrian Arab Air Force, departing from Shayrat airbase, dropped an M4000 aerial bomb containing sarin in southern Ltamenah, affecting at least 60 persons.

The IIT document further noted that

the sarin in question is consistent with the sarin of the stockpile and the production processes of the Syrian Arab Republic. In particular, the IIT concluded that the chemical profile (i.e., a collection of chemicals) of the sarin used in Ltamenah on 24 and 30 March 2017 strongly correlates to the chemical profile expected for sarin produced through a binary reaction in which the key binary component (DF) is manufactured via routes, as well as by using precursors and raw materials, pursued by the Syrian Arab Republic in its sarin programme. The IIT received no information that the sarin found in Ltamenah could have been developed in this way elsewhere, yet resulting in the ‘signature’ evidenced by that specific collection of chemicals. On the basis of the investigations of the IIT, this type of sarin is not known to have been developed and manufactured by States or entities other than the authorities of the Syrian Arab Republic. (Document S/1867/2020, 8 April 2020, para. 11.3)

It also pointed out parallels with the findings of the JIM report on the CW attack in Khan Shaykhun days after the strikes against Ltamenah:

The IIT further compared the chemical ‘signature’ identified in the samples of the March 2017 Ltamenah incidents to results of analyses from samples from other sarin incidents. A comparison of the results of analysis of samples collected during the Ltamenah incidents, on the one side, with the analytical results of samples collected in relation to the Khan Shaykhun incident of 4 April 2017, on the other side, shows significant similarities. Indeed, the analytical results from these three incidents are consistent with sarin resulting from a binary process using the DF from the Syrian Arab Republic stockpile. Finding together certain chemicals in samples collected from the incidents suggests the same source of sarin. The finding of the same chemicals associated with sarin in these incidents, and previous ones in the territory of the Syrian Arab Republic to which the IIT had access, strongly indicates that the sarin used in all of them was manufactured through the same process. (Ibidem, para. 11.8)

The report also excluded the possibility that insurgents or rogue units might have got hold of the CW and used them.

Nature of the conclusion in the IIT report

The IIT is a non-judicial investigative mechanism with a specific mandate, namely to identify actors – natural and legal persons, organisational units or other entities – and the complex of their respective and mutually supportive roles in the use or preparations for CW use. Its conclusions may serve as foundation for action by OPCW members based on their determination of a major breach of the CWC (and its Article I in particular) or support future criminal proceedings before an international criminal court on war crimes in the Syrian civil war. Like the JIM before it, the IIT cannot make a formal or binding judicial finding of criminal liability:

The IIT is not a judicial investigative body. As such, the IIT does not possess the authority to gather evidence in the same manner as prosecutorial offices, courts, and tribunals, nor does it have the authority and jurisdiction to issue judicial determinations or other legally binding verdicts on criminal responsibility. The non-judicial nature of the IIT is comparable to that of international fact-finding bodies or commissions of inquiry. (Document S/1867/2020, 8 April 2020, para. 1.7)

The IIT analyses, verifies and corroborates facts as presented by the FFM to identify the perpetrators of CW use. It should also collect and report on all information it considers potentially relevant to the origin of those CW. The work involves assessing reliability and strength of evidence against a presumed perpetrator.

Terminology to express confidence in the strength of the evidence may differ from organisation to organisation or depend on the purpose of the assessment. For example, as set out in its first report to the UNSC (Document S/2016/142, 12 February 2016), the JIM Leadership Panel adopted these standards:

(a) Overwhelming evidence (highly convincing evidence to support a finding);

(b) Substantial evidence (very solid evidence to support a finding); or

(c) Sufficient evidence (there is evidence of a credible and reliable nature for the Mechanism to make a finding that a party was involved in the use of chemicals as weapons).

Regarding the Khan Shaykhun investigation, it determined that the information it obtained ‘constitutes sufficient credible and reliable evidence’ and concluded that ‘the Syrian Arab Republic is responsible for the release of sarin’ on 4 April 2017.

In contrast, the IIT only uses a single standard for its reports: ‘reasonable grounds’, which it circumscribes as follows

Following standard practice of international fact-finding bodies and commissions of inquiry, the IIT will only reach conclusions on the identification of perpetrators on the basis of a sufficient and reliable body of information which, consistent with other information, would allow an ordinarily prudent person to reasonably believe that an individual or entity was involved in the use of chemical weapons (i.e., ‘reasonable grounds’). Thus, under this degree of certainty, an objective observer would reasonably conclude that a violation was committed. (Document S/1867/2020, 8 April 2020, para. 2.18)

It further clarified that

This is a generally accepted approach of fact-finding bodies and commissions of inquiry, in particular when individuals are to be identified in relation to extremely serious allegations (such as the use of chemical weapons) warranting further investigation and prosecution by competent judicial bodies. This degree of certainty is consistent with the standards used in domestic and international criminal prosecutions. It would also not be inconsistent with the requirement for the Secretariat to inform the Council of ‘doubts, ambiguities or uncertainties’ about compliance with the Convention by States Parties. (Ibid., para. 2.19)

Use of the phrase follows Article 58 of the 1998 Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court.

Details and broad strokes

As pointed out above, the IIT concluded there are reasonable grounds to believe that the government forces were responsible for the Ltamenah incidents. It identified units and bases from which the aircraft departed.

The report authors also posited that the investigated military operations would require orders from the highest military authorities. The assertion is consistent with the observation that irrespective of the political system, CW use has always required authorisation from a country’s highest political or military authorities. Conventionalisation of chemical warfare during the latter part of the First World War has so far been the only exception. However, the IIT lacked sufficient information to draw definite conclusions about the specific chain of command in the three Ltamenah incidents.

Still, if government forces bear responsibility for the CW attacks against Ltamenah, then Syria must have run an armament programme too. The latter is a complex undertaking involving multiple clusters of activities and different actor types. Syria has therefore either not declared the full extent of its CW programmes, stockpiles of agents or precursors, means of delivery, and installations for synthesising, storing or filling toxic chemicals into munitions; or it has reconstituted parts of its former CW programme. The public OPCW documents do not reveal the provenance of chlorine and sarin used in Ltamenah or indicate the places where the chemical munitions might have been manufactured. The government has refused the FFM access to named military airbases and rejects cooperation with the IIT.

Violation of Article I, para. 1(b) to never under any circumstances use CW entail breaches of paras. 1(a) and 1(c) prohibiting respectively the development, acquisition and possession of CW, and military preparations for CW use. Since Syria joined the CWC in October 2013, the Technical Secretariat has repeatedly informed the OPCW that despite many meetings between the DAT and Syrian officials it cannot verify and certify the accuracy and completeness of the country’s declaration in line with the convention and the Executive Council decision on CW destruction (Document EC-M-33/DEC.1, 27 September 2013).

The IIT’s first investigative report is in that sense also the most direct accusation that Damascus either did not declare and destroy all production installations, munitions and chemicals, or has resumed a CW armament programme in blatant violation of the treaty and relevant UNSC resolutions.

Possible future legal action

Whether Syrian government officials and military commanders will appear before the International Criminal Court or a special war crimes tribunal depends on future decisions by the international community. To support future action, the special session of the Conference of the States Parties specifically determined that the Technical Secretariat, and therefore the IIT, preserve and inform the International, Impartial, and Independent Mechanism established by the UN General Assembly (UNGA) under Resolution A/RES/71/248 (2016), or any other relevant investigatory body set up under UN auspices.

A future prosecutor could thus request the court to issue an arrest warrant or summons to appear before it based on the IIT’s belief there exist ‘reasonable grounds’ that a given person committed a crime within the jurisdiction of such a tribunal.

While the IIT report does not establish criminal guilt of a perpetrator, it lays the foundation for future prosecution.

Supplementary actions by the Executive Council

CWC Article VIII, para. 36 is one of the provisions that define the powers and functions of the Executive Council:

In its consideration of doubts or concerns regarding compliance and cases of non-compliance, including, inter alia, abuse of the rights provided for under this Convention, the Executive Council shall consult with the States Parties involved and, as appropriate, request the State Party to take measures to redress the situation within a specified time. To the extent that the Executive Council considers further action to be necessary, it shall take, inter alia, one or more of the following measures:

(a) Inform all States Parties of the issue or matter;

(b) Bring the issue or matter to the attention of the Conference;

(c) Make recommendations to the Conference regarding measures to redress the situation and to ensure compliance.

The Executive Council shall, in cases of particular gravity and urgency, bring the issue or matter, including relevant information and conclusions, directly to the attention of the United Nations General Assembly and the United Nations Security Council. It shall at the same time inform all States Parties of this step.

Drawing on it, the Executive Council decided that to redress the situation Syria must within 90 days (Document EC-94/DEC.2, 9 July 2020)

(a) declare to the Secretariat the facilities where the chemical weapons, including precursors, munitions, and devices, used in the 24, 25, and 30 March 2017 attacks were developed, produced, stockpiled, and operationally stored for delivery;

(b) declare to the Secretariat all of the chemical weapons it currently possesses, including sarin, sarin precursors, and chlorine that is not intended for purposes not prohibited under the Convention, as well as chemical weapons production facilities and other related facilities; and

(c) resolve all of the outstanding issues regarding its initial declaration of its chemical weapons stockpile and programme.

The Director-General must furthermore report within 100 days whether Syria has complied with those demands and must update the Executive Council at all its regular sessions on progress if the country had not completed the demands. He must also submit a copy of the decision with associated reports to the UNSC and UNGA via the UN Secretary-General.

The Executive Council also decided to bring the matter before the next Conference of the States Parties and threatened further action under CWC Article XII, para. 2:

In cases where a State Party has been requested by the Executive Council to take measures to redress a situation raising problems with regard to its compliance, and where the State Party fails to fulfil the request within the specified time, the Conference may, inter alia, upon the recommendation of the Executive Council, restrict or suspend the State Party’s rights and privileges under this Convention until it undertakes the necessary action to conform with its obligations under this Convention.

The 25th session of the Conference of the States Parties is due to take place from 30 November to 4 December 2020.

Finally, the Executive Council directed the Technical Secretariat to conduct twice each year inspections at the airbases identified in the IIT report ‘with full and unfettered access to all areas, buildings and structures at these sites, including all rooms within buildings, as well as to their contents and to personnel’ until when it decides to cease them. It also demanded prompt facilitation and full cooperation from Syria.

With these demands, the Executive Council clearly aims to uncover the full extent of the CW armament programme behind the chemical strikes against Ltamenah.