Novichok and the Chemical Weapons Convention

Assassinations with nerve agents are rare. Very rare. The reason is simple: other means to eliminate a person are simpler and much more effective. The marginal benefit from using even some of the most toxic substances ever made by man is negligible. What is more, the attempt fails often, as Aum Shinrikyo experienced when trying to take out some of the cult’s enemies with VX before the 1995 sarin attack in the Tokyo underground. Last year’s murder of Kim Jong-nam, half-brother of North-Korean leader Kim Jong-un, also involved VX according to Malaysian authorities. However, the real perpetrator behind the two women who rubbed the substance in his face was quickly identified.

The surprise that the assassination attempt on former Russian spy Sergei Skripal and his daughter Yulia in Salisbury, UK on 4 March involved one of the Novichoks was not little. First, this family of nerve agents is relatively unknown. Outside specialised disarmament and HazMat communities few people would have been aware of its existence. Over 100 chemical structures are believed to belong to it, all related yet different. The group of chemical structures does not figure in the Annex on Chemicals of the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC). Second, the substance was produced in any sizeable quantities in only one single country, the Soviet Union. Third, the required precursor chemicals and the pathways to synthesise the final agents are completely obscure to most of the public.

The UK government has formally accused Russia of the assassination attempt and expelled 23 Russian diplomatic personnel. Moscow vehemently denies the accusal and has retaliated by demanding that a similar number of diplomats leave the country. It furthermore denies ever having developed and produced Novichoks. The incident follows an already bitter stand-off between the West and Russia over Syria’s proven chemical weapon (CW) use that blocks effective UN Security Council action and splits the Executive Council (EC) of the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW). As the government of Prime Minister Theresa May has formally declared its intention to have the OPCW independently verify its analyses and share it with its international partners, the question is whether and how the international organisation can contribute to resolving the matter.

Ensuring compliance under the CWC

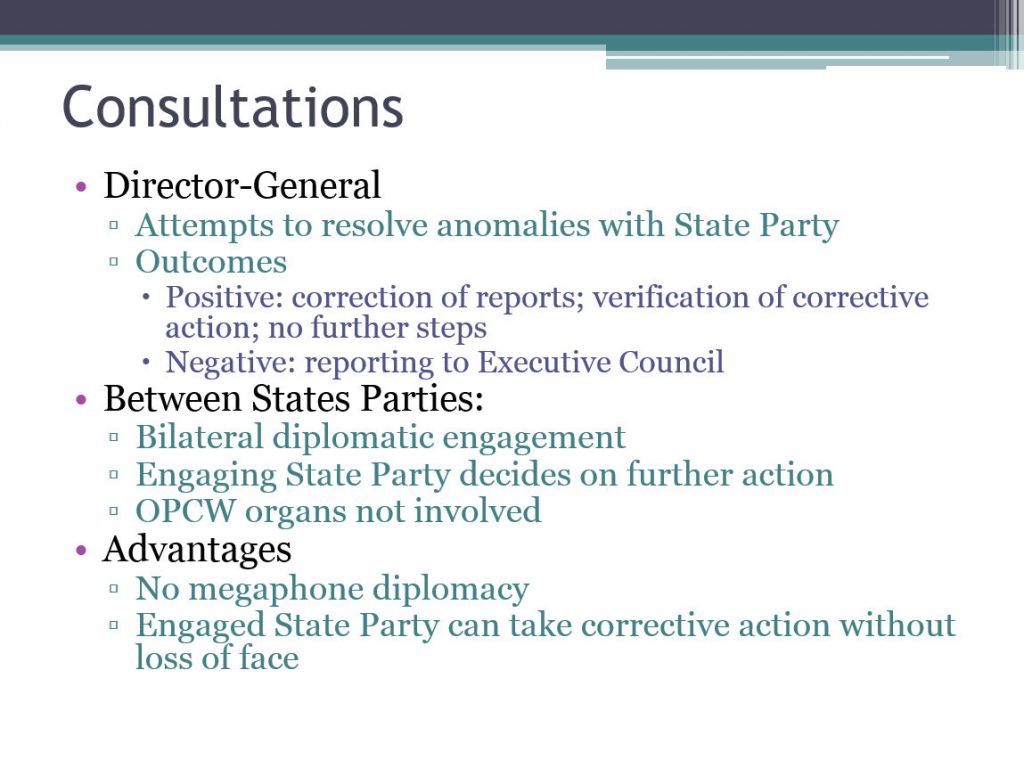

Beyond the CWC’s routine verification process involving declarations, assessments and inspections, Article IX ‘Consultations, Cooperation and Fact-Finding’ foresees procedures to resolve uncertainties about compliance or breaches of the convention. These procedures are consultations, clarification, challenge inspection and investigation of alleged use.

Consultation concerning anomalies

The CWC does not detail what consultations should entail, but views and encourages them together with information exchanges as one of the early (or low-key) diplomatic exchanges among states parties to resolve doubts or ambiguities about compliance.

According to a statement issued by the UK’s Foreign and Commonwealth Office, on 12 March Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson summoned the Russian Ambassador to seek an explanation from the Russian Government. The statement strongly suggests that the step was undertaken under the consultative process foreseen under Article IX. It added that Russia provided no meaningful response.

Clarification of compliance concerns

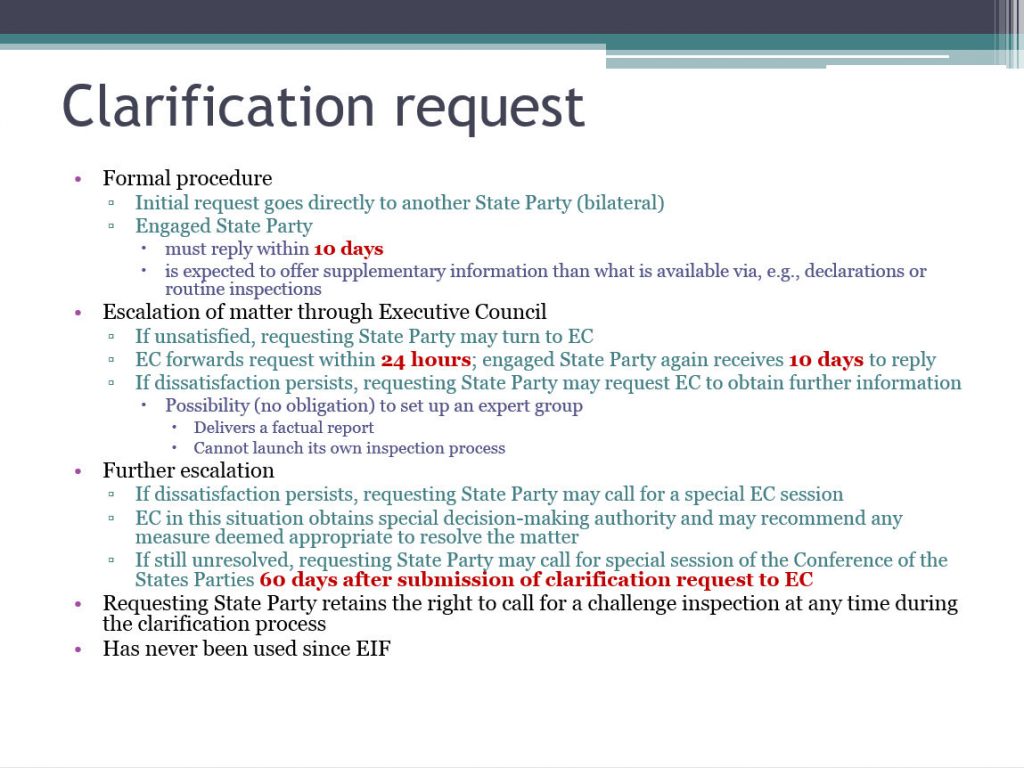

If in doubt or concerned about compliance, a state party may seek clarification. A state party will address the initial request for clarification to another state party, who must reply within 10 days. Although not stipulated in the convention, a degree of expectation exists that the latter would supply supplementary information (i.e. beyond what is available from, for instance, annual declarations or routine inspections) to address the concern.

In case the reply does not resolve the concern, the requesting state party may call for assistance from the EC, which must use its authority to lend weight to the request, including through forwarding the request within 24 hours. The state party to whom the clarification request is addressed has once again a maximum of 10 days to respond. If the replies still do not satisfy, the requesting state party my next request the EC to obtain further information, in which case it may (not ‘must’) decide to set up a group of experts to examine all available information and reports and submit a factual report. Although the group of experts can draw on previous inspection reports, it is in no position to launch its own inspection procedure.

After either of the two previous steps, the requesting state party may call for a special session of the EC, which then has the decision authority to ‘recommend any measure it deems appropriate to resolve the situation’. Although not stated explicitly in Article IX, those measures would presumably include obtention of further information or persuasion of the targeted state party to resolve the presumed violation in accordance with the CWC. If the requesting state party remains unsatisfied with the response, it may call for a special session of the Conference of States Parties (CSP) 60 days after the submission of the request for clarification to the EC. The CSP is to consider and may take any measure, which, as in the case of the EC, remains unspecified in the convention.

It is important to note that the launch of a clarification procedure does not require the outcome of routine inspections, but inspection reports may trigger additional requests for information. It should also be noted that the procedures described above do not affect the requesting state party’s right to call for a challenge inspection, nor are they affected by the conduct of a challenge inspection.

Challenge of non-compliance

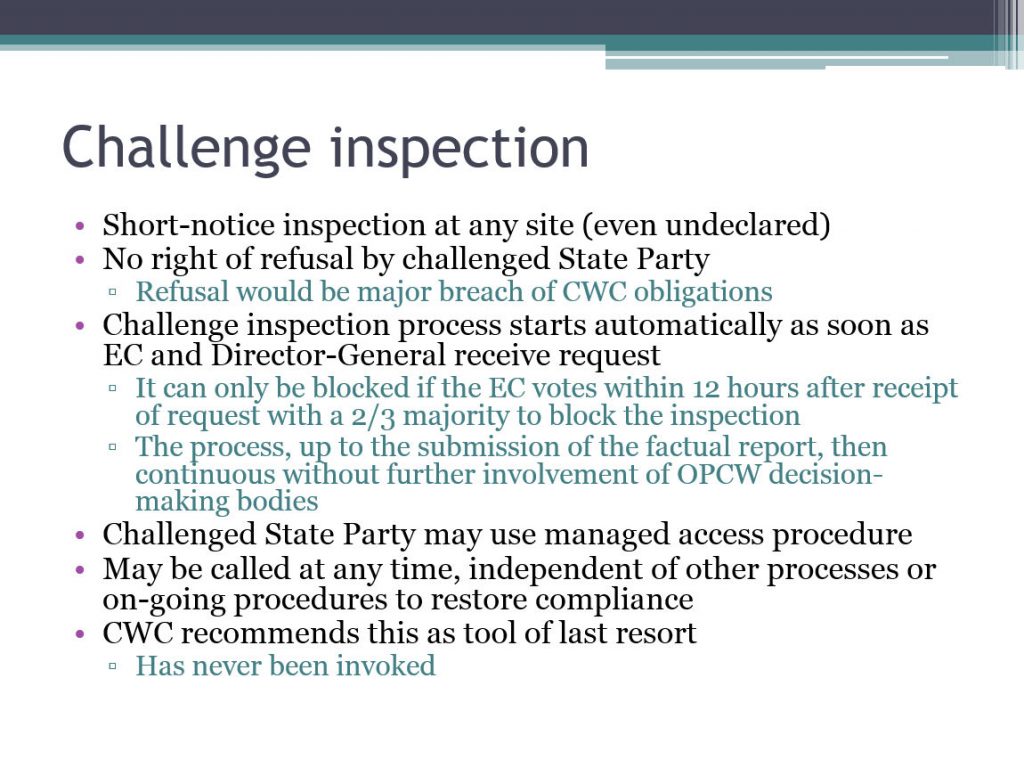

Challenge inspections are the third tool outlined in CWC Article IX. It consists of a short-notice inspection at any site (irrespective of whether it has been declared or not) in a state party. Once the OPCW has authorised the challenge inspection the targeted state party has no right of refusal, but it can invoke the technique of managed access through which OPCW inspectors may be denied access to certain parts of the site. Managed access cannot be implemented in such a way that inspector access to the site as such is denied. However, irrespective of the outcome of the managed access negotiations between representatives of the challenged stated party and the OPCW inspectors, the latter retain full right to interview any staff member of the site (and thus possibly obtain relevant information about the areas to which they have been denied access).

Although a challenge inspection can be requested at any stage of consultation of clarification processes, the CWC encourages states parties to view the tool as an instrument of last resort.

Investigation of alleged use

Part XI of the Verification Annex details the process of investigating the alleged use of CW or the alleged use of riot control agents as a method of warfare. In case the alleged use involves a state not party to the CWC, then the Director-General of the OPCW will closely cooperate with the UN Secretary General.

The procedure is applied (and has been further developed) with respect to the many allegations of chemical warfare in Syria. It is less relevant to the Novichok case.

Pathways to resolving the Novichok matter

How the investigation of the Skripal assassination attempt plays out will largely depend on the next key decisions by the UK government. The OPCW experts travel to the UK under Article VIII, 38(e), which qualifies their activity as a ‘Technical Assistance Visit’ to help with the evaluation of an unscheduled chemical (the Novichock agent) is not listed in any of the three schedules in the Annex on Chemicals). They will likely visit the sites of investigation and collect their own samples (if for no other reason than to validate any laboratory samples they may receive), take all materials and documents related to the forensic investigation back to the Netherlands where the sample will be divided up and sent to two or more designated OPCW laboratories. (The list for 2017 can be consulted here.)

After having received the report, the UK government may opt to pursue the case using its own diplomatic means, possibly together with its allies, or it may decide to invoke one of the procedures outlined above, the most likely one being the clarification process. Given the current level of political rhetoric and the earlier summons of the Russian Ambassador, consultations will have little utility left. To call for a challenge inspection the UK will need to have extraordinarily precise information about the production or storage location (which might be difficult if, for example, forensic analysis points to recent, small-scale synthesis of Novichok or to a chemical structure different from those associated with the Soviet programme).

At present the outcome of any one of the procedures is difficult to foresee. Neither the clarification process nor challenge inspection option have been invoked previously. Moreover, even though the CWC may at first sight seem to suggest a hierarchy among the different procedures in terms of increasing stringency or steps in an escalatory process, each one can be pursued independently. They may also be invoked in succession, or they can run in parallel. One procedure is not necessarily a prerequisite to another one.

Central to the understanding of the procedures is that the OPCW, as an independent international organisation dedicated to overseeing the implementation of the CWC, provides a forum for consultation and cooperation among states parties, also in matters concerning compliance or conflict resolution.

2 Comments

Links – March 30, 2018 |

[…] Jean Pascal Zanders is your reliable go-to for information on how all this fits into the Chemical Weapons Convention. Here’s one of his posts on the subject at his blog. […]

SECURE SYNOPSIS: 28 MARCH 2018 - INSIGHTS

[…] Reference […]