History of nerve agent assassinations

On 20 August, the Russian anti-corruption activist Alexei Navalny fell ill during a return flight to Moscow and was hospitalised in the Siberian town of Omsk after an emergency landing. Members of his travelling party immediately suspected poisoning, an impression hospital staff reinforced when they refused Navalny’s personal physician access to his medical records.

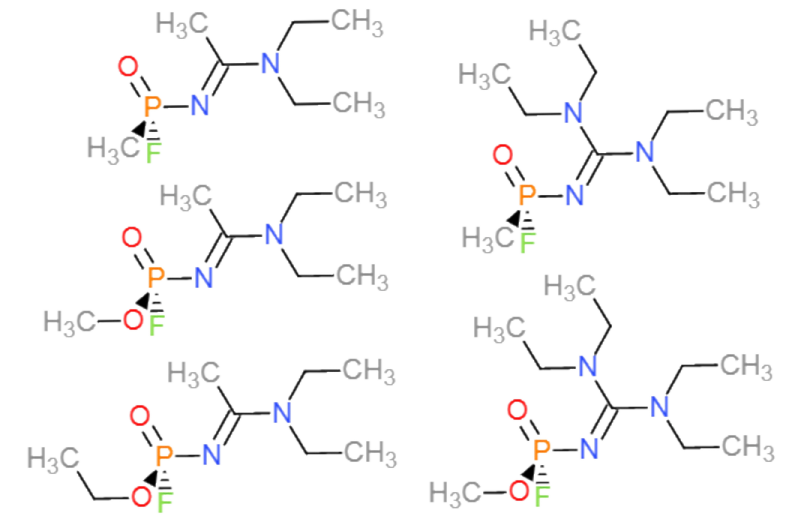

Following his airlifting to Berlin for further examination and specialist treatment, the Charité hospital issued a statement on 24 August that preliminary findings indicated exposure to ‘a substance from the group of cholinesterase inhibitors’. Even though the hospital could then not name the specific poison used, it added that multiple tests by independent laboratories had confirmed the effect of the poison. The hospital was also treating him with the antidote atropine. The references to a cholinesterase inhibitor and atropine were the first strong indicators of a neurotoxicant, to which nerve agents like sarin, VX or the novichoks belong.

A week later, on 2 September, German Chancellor Angela Merkel confirmed the assassination attempt with a novichok agent at a press conference. She drew on the conclusions from biomedical analyses by the Institut für Pharmakologie und Toxikologie der Bundeswehr (Bundeswehr Institute of Pharmacology and Toxicology), one of the top laboratories designated by the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons to investigate biomedical samples.

From natural poisons to warfare agents

Poisoning political opponents or enemies is not new. In his almost 600 pages-long ‘Die Gifte in der Weltgeschichte’ (1920) the German pharmacologist Louis Lewin detailed chapter after chapter how besides criminals and spurned lovers, rulers, leaders, undercover agents and conspirators applied the most noxious substances in pursuing domestic political or international geopolitical objectives. Reviews of chemical and biological weapons (CBW) usage through the 20th century similarly list successful and attempted assassinations with mineral poisons or animal and plant toxins in and outside of war.

Modern chemical weapons (CW) – typically human-made toxic compounds standardised for use on battlefields – have rarely been selected to target individuals. Observers and journalists reported first use of nerve agents by Iraq against Iran in 1983, almost five decades after their initial discovery in Nazi Germany. In March 1995 the world learned of Aum Shinrikyo after its members had released the nerve agent sarin in the Tokyo underground. However, during the previous eight months the extremist cult had also resorted to both sarin and VX in attempts to assassinate judges about to rule against Aum Shinrikyo and individuals who posed a threat or had defected from the religious group. These were the first and for more than a decade and a half the only reports of neurotoxicants used to murder individuals.

The Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) eliminated Kim Jong-nam, half-brother of North Korean leader Kim Jong-un, with a binary form of VX in February 2017. Just over a year later, in March 2018, Russian operatives attempted to murder a former double agent Sergei Skripal in Salisbury, UK with a nerve agent belonging to the lesser known family of so-called ‘novichoks’ (newcomer). Skripal’s daughter and a police officer were also exposed to the toxicant. They too survived. In June two British citizens fell ill in the nearby town of Amesbury because of exposure to the agent in a small bottle discarded by the Russian agents. One exposed person succumbed.

Following the Skripal case the Bulgarian Prosecutor General reopened a poisoning case in October 2018 at the request of the victim, arms manufacturer and trader Emilian Gebrev. The assassination attempt dated to April 2015. Also exposed were his son and the production manager of the Dunarit munitions factory. The Prosecutor General confirmed that a Russian operative linked to the Skripal attempt had visited Bulgaria at the time of the incident. Subsequent forensic analysis of serum and urine samples from Gebrev by the Finnish laboratory VERIFIN confirmed the poisoning. According to the UK-based CW expert Dan Kaszeta, who read a copy of the report, the Finnish institute intimated that Gebrev might have been exposed to an organophosphate pesticide. A Bulgarian news outlet has suggested the agricultural insecticide Amiton (also known as Tetram). Now commercially banned because of its high toxicity, in the 1950s the UK investigated its use as a nerve agent under the code VG.

Some reports have also claimed that Aum Shinrikyo murdered around 20 dissident members and defectors with VX in one of the cult’s compounds. To the best of my knowledge no documentary evidence to support the claim has been published.

Previous assassination operations involving nerve agents

Nerve agents were battlefield weapons, mostly liquids of different viscosity. The volatile sarin could prepare the pathway of an attack, whereas the oilier tabun and VX had their greatest utility as area denial weapons for defending terrain or protecting flanks during an advance. Their manufacture in large volumes is complex and maintaining their stability during longer-term storage is a hurdle that even few states have satisfactorily crossed. In laboratory volumes, a skilled chemist may be able to synthesise agent of high purity. But this person would have to take the greatest precautions to avoid inadvertent exposure to its noxious properties. While the relatively high toxicity of nerve agents may appear attractive to terrorists or assassins, the marginal benefit they offer over other terrorist or criminal tools is usually too small to make the investments or risks worthwhile. Hence, their use by terrorists or criminals has been rare.

Until recently, their use in assassination operations would have been considered even rarer, especially because of the poor results obtained by the Japanese cult Aum Shinrikyo in the first half of the 1990s.

The following table summarises known assassination operations with neurotoxicants.

| Date | Perpetrator | Comments |

| 27 June 1994 | Aum Shinrikyo | Sarin released in Matsumoto from a converted lorry to kill three judges who were to rule in a land dispute. They survived. However, the drifting sarin cloud eventually killed eight persons and injured over 500. |

| Autumn 1994 | Aum Shinrikyo | Suspected VX attack against Taro Takimoto, lawyer for Aum victims. The agent had been applied on the handle of his car door. Failed, reasons unknown |

| Autumn 1994 | Aum Shinrikyo | Second suspected VX attack against Taro Takimoto. The agent had been inserted into a keyhole. Failed, reasons unknown. (Aum reportedly also attempted to murder this person with botulinum toxin around this time.) |

| 28 November 1994 | Aum Shinrikyo | VX squirted from a syringe onto Noboru Mizonu in retaliation for offering shelter to former Aum members. Failed. |

| 2 December 1994 | Aum Shinrikyo | Second attack on Noboru Mizonu with VX delivered drop by drop from a syringe. Hospitalisation for 45 days required. |

| 12 December 1994 | Aum Shinrikyo | VX injected with a syringe into Tadahito Hamaguchi in Osaka, having been misidentified as a police spy. First person ever to have been deliberately killed with VX. |

| 4 January 1995 | Aum Shinrikyo | VX syringe attack against the head of the Aum Victims Society, Hiroyuki Nagaoka. Hospitalised for several weeks. |

| 1 August 1995 |

Russia |

Telephone of Ivan Kivelidi, founder of Rosbiznesbank, laced with a toxic substance. He died; his secretary, Zara Ismailova, died two days later. In 2018, after the Skripal poisonings, former chemical weaponeer Vladimir Uglev, identified the poison as one of the novichoks. |

| 28 April 2015 | Russia | Bulgarian arms trader Emilian Gebrev poisoned with an organophosphorus compound. Two other persons present also suffered consequences. Following the Skripal case in March 2018, a possible link to novichok has been suggested but not confirmed. Bulgaria charged three Russian operatives with attempted murder in January 2020, one of whom is also a suspect in the Skripal case. |

| 13 February 2017 | DPRK | Attack with binary VX on Kim Jong-nam, half-brother of Kim Jong-un, DPRK leader, at Kuala Lumpur International Airport, Malaysia. Killed. |

| 4 March 2018 | Russia | Assassination attempt with a novichok agent, presumed to be A-234, on former Soviet/Russian intelligence officer, Sergei Skripal, in Salisbury, UK. His daughter Yulia was also exposed to the neurotoxicant, which Russian operatives had applied to the door handle of Skripal’s home. Detective Sergeant Nick Bailey too suffered effects from exposure. All three persons recovered after multiple weeks in hospital. |

| 30 June 2018 | Russia | Charlie Rowley and Dawn Sturgess were hospitalised in the nearby town of Amesbury following inadvertent exposure to novichok after having recovered a vial discarded by the Russian operatives. Sturgess died on 8 July; Rowley recovered after hospitalisation. |

| 20 August 2020 | Russia | Assassination attempt on Russian opposition politician Alexei Navalny with a novichok agent, presumed in powdered form, at Tomsk airport, Russia. Still hospitalised in Berlin at the time of writing. |

| [Sources: Anthony T. Tu, The use of VX as a terrorist agent (2020); Monterey Institute of International Studies, Chronology of Aum Shinrikyo’s CBW Activities (2001); and assorted press reports.] | ||

There have been 13 incidents with neurotoxicants. Twelve persons were the direct target, of whom three died.

Around 520–530 other individuals in total suffered exposure to the poisonous substances. Ten among them died. Aum Shinrikyo’s sarin cloud attack against the judges’ dormitory in Matsumoto caused almost all collateral casualties.

Seven persons other than the immediate targets fell victim to Russian operatives, two of whom succumbed to the poisoning.

Only in one listed operation (Gebrev) remains the use of a military type of nerve agent unconfirmed. In another case (Kivelidi) the identification of novichok is based on a press interview with a former participant in the development of novichoks more than two decades after the incident. No scientific analyses supporting the charge are publicly available.

[Updated on 11 September 2020 to include the Kivelidi case (August 1995)]

5 Comments

Biological Weapons in the 'Shadow War' - War on the Rocks

[…] allies or proxies/surrogates in a region). However, the recent chemical weapons use in assassinations and the use of chemical weapons in Syria — followed by a tepid international response — likely […]

Biological Weapons in the ‘Shadow War’ | taktik(z) GDI (Government Defense Infrastructure)

[…] allies or proxies/surrogates in a region). However, the recent chemical weapons use in assassinations and the use of chemical weapons in Syria — followed by a tepid international response — likely […]

Biological Weapons in the 'Shadow War' - War on the Rocks - International News

[…] allies or proxies/surrogates in a region). However, the recent chemical weapons use in assassinations and the use of chemical weapons in Syria — followed by a tepid international response — likely […]

Biological Weapons in the 'Shadow War' – War on the Rocks – Daily Research

[…] allies or proxies/surrogates in a region). However, the recent chemical weapons use in assassinations and the use of chemical weapons in Syria — followed by a tepid international response — likely […]

Biological Weapons in the ‘Shadow War’

[…] allies or proxies/surrogates in a region). However, the recent chemical weapons use in assassinations and the use of chemical weapons in Syria — followed by a tepid international response — likely […]