Investigation of alleged chlorine attacks in the Idlib Governorate (Syria) in March – May 2015

On 29 October, the Technical Secretariat of the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) circulated three reports on investigations of alleged chemical weapons (CW) use in Syria. On 5 November Reuters published some details from the one addressing the alleged use of sulphur mustard agent in Marea, a town to the north of Aleppo, on 21 August. The two other reports address a series of incidents between 15 December 2014 and 15 June 2015 at the request of the Syrian government and between 16 March and 20 May 2015 in the Idlib Governorate documented by a variety of non-governmental sources.

For the purpose of clarity, the OPCW maintains a single Fact-Finding Mission (FFM), which has so far produced six reports. Under the FFM, the OPCW may deploy different teams to different locations.

The most recent reports will be released as part of the monthly OPCW reports on Syria to the UN Security Council, presumbly at the end of this month following the special session of the Executive Council on 23 November called to consider the findings.

Incidents in Idlib Governorate, March – May 2015

The Idlib Governorate lies to the south-west of Alleppo. During the spring of 2015 the international press and social media reported a string of incidents suggesting the use of chlorine as a weapon.

This team of the Fact-Finding Mission received its mandate to investigate incidents involving the use of toxicants as a weapon based on open-source media, other sources of information and materials obtained from non-governmental organisations. The investigation could not take place under optimal conditions, because the OPCW inspectors were unable to visit the sites of alleged incidents shortly after their occurrence, take their own samples or review the records onsite. Instead they based themselves on interviews and supplementary materials submitted during the interview process. They were nevertheless able to conclude:

In itself, no one source of information or evidence would lend particularly strong weighting as to whether there was an event that had used a toxic chemical as a weapon. However, taken in their entirety, sufficient facts were collected to conclude that incidents in the Syrian Arab Republic likely involved the use of a toxic chemical as a weapon. There is insufficient evidence to come to any firm conclusions as to the identification of the chemical, although there are factors indicating that the chemical probably contained the element chlorine.

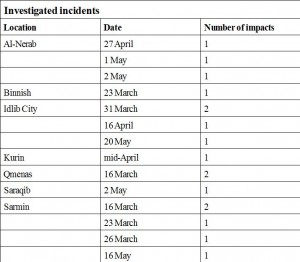

The report documents 17 incidents in 6 locations between 16 March and 20 May 2015. They were responsible for six fatalities.

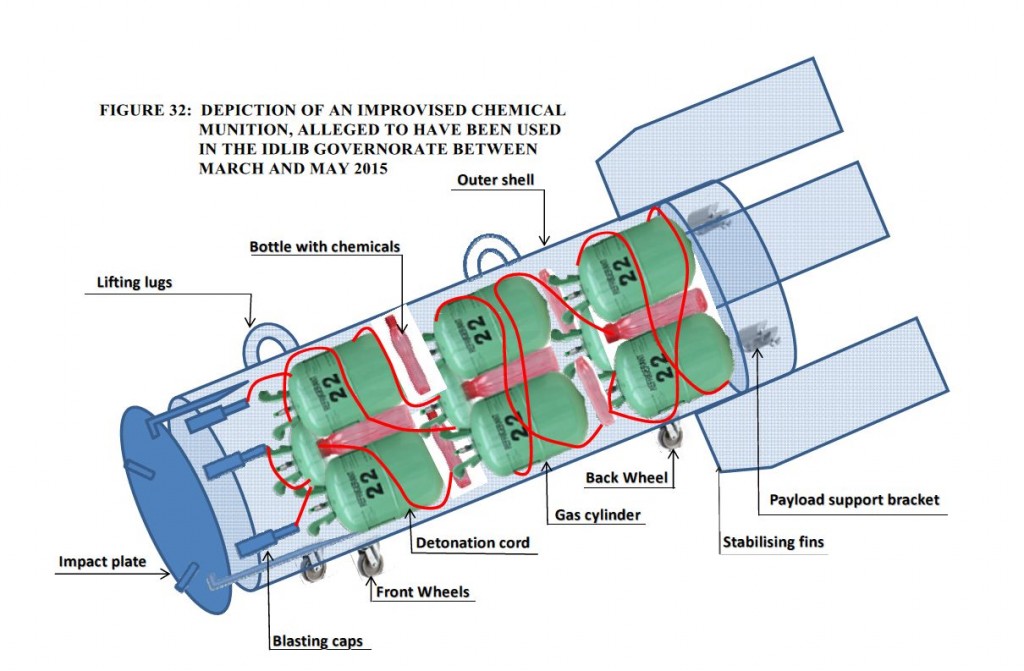

First depiction of a chemical barrel bomb dropped from helicopters

The report also included a depiction of a so-called barrel bomb, based on the various testimonials and collection of bomb fragments. It notes that the design of the improvised weapon underwent an evolution of their manufacture, probably driven by trial and error. However, only a singly type appears to have been used in the Idlib Governorate between March and May 2015.

The configuration consists of 9 gas cylinders (green) presumably filled with poisonous chemicals. The report suggests that they may have been filled with a chlorine or chloride containing compound. The flasks with potassium permanganate (pink) would then have been used to oxidise the chlorine containing compound, resulting in Cl2. The potassium permanganate may be responsible for the purple–red colour occasionally seen in pictures and video footage of impact sites.

This depiction definitely explains how high concentrations of chlorine were achieved locally, earlier assessments of improbability having been based on the assumption of the dropping or firing of single gas cilinders fitted with a light detonator. Interestingly, the barrel bomb configuration would not have contradicted this assumption, given the individual rigging of gas cylinders (see Brown Moses’ speculation on this in 2014) and the focus of outside observers on those cylinders. To the best of my recollection, only a single report on developments in Syria in 2014 prepared by Human Rights Watch made a passing reference to the possibility: ‘evidence strongly suggests that Syrian government helicopters dropped barrel bombs embedded with cylinders of chlorine gas on three towns in Northern Syria in mid-April‘.

On the value of the evidence

As usual and for good reason, the reports by the Technical Secretariat remain careful in their conclusions. Determination of reponsibility for the violation of the Chemical Weapons Convention and other legal instruments banning chemical warfare is pre-eminently a political judgement. As noted earlier, the Executive Council will consider these findings (as well as those in the other two reports) on 23 November, after which they will be transferred to the UN Security Council. They will also inform the Joint Investigative Mission established by the UNSC in August, whose principal task it is to determine responsibility for chemical warfare in the Syrian civil war.

Meanwhile, the investigators assess their findings concerning the delivery system as follows:

The description of the alleged chemical weapon and its deployment derives from several inputs, as previously described. The features of the improvised chemical bomb are consistent with its being designed for deployment from a height. As most incidents happened during darkness, it is not surprising that no interviewees claimed to have seen the means of deployment. The deformation of the remnants is consistent with mechanical impact and explosive rupture, rather than explosion causing deflagration. Witnesses also reported a lesser explosive sound than for other more conventional types of bombs. Moreover, casualties’ signs and symptoms do not include physical injuries that would be expected from the deployment of an explosive device. The craters which have been claimed to have been caused by the device are also consistent with its being dropped from a height with lesser explosive power. It is therefore reasonable to assume that the devices were not designed to cause mechanical injury through explosive force but rather to rupture and release their contents.

4 Comments

pmr9

If this diagram is really in an OPCW report, the credibility of the FFM is called into question.

1. The reaction of potassium permanganate with hydrochloric acid is an impractical way to deliver chlorine, though it’s a convenient way to prepare small quantities in the lab. An ordinary cylinder of liquid chlorine would deliver far more chlorine for the same payload. The design as shown doesn’t allow the reactants to mix before detonation, so the yield would be very low

3. The stoichiometry is all wrong – the reaction requires potassium permanganate and hydrogen chloride in the ratio approximately 1:2 by weight. The solubility of potassium permanganate in water is only one-tenth that of hydrogen chloride, so the ratio by volume would be 5:1. In the design shown, this ratio is about 1:20.

There are other reasons to doubt the story of the alleged chlorine attacks. Specifically, examination of the videos from the alleged attack in Sarmin on 16 March 2013 [http://libyancivilwar.blogspot.co.uk/2015/04/what-killed-talebs.html] has shown that:-

1. The clinical signs in the child whose death is shown in the video are consistent with a drug overdose causing respiratory depression, rather than chlorine poisoning.

2. The staff make no attempt to provide respiratory support when this child stops breathing, though they are in a well-equipped emergency room.

2. The apartment where the family is supposed to have lived is empty when the rescuers arrive, with blood on the floor in several rooms.

3. The videos released by the purported civil defense organization White Helmets share content with those released by the Al-Nusra Front, the Syrian affiliate of Al-Qaeda.

Investigation of alleged chlorine attacks in th...

[…] On 29 October, the Technical Secretariat of the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) circulated three reports on investigations of alleged chemical weapons (CW) use in Syria.… […]

CW incidents alleged by the Syrian government: an industrial chemical as likely cause? | The Trench

[…] previous posting (16 November) presented the findings by the Fact-Finding Mission (FFM) of the Organisation for the […]

CW incidents alleged by the Syrian government: an industrial chemical as likely cause? | Arms Control Law

[…] previous posting (16 November) presented the findings by the Fact-Finding Mission (FFM) of the Organisation for the […]